Back when I was young, SF was a comparatively obscure genre. Many librarians assumed that it was all kid stuff, and filed it as such. Consequence: I was allowed to check out and read books that would otherwise have been considered totally inappropriate for young kids1. Which is not to say I didn’t benefit from reading some of those books, but I am pretty sure that if my librarians and teachers2 had had any idea what those books were, they would have been aghast. (Possibly two ghasts!)

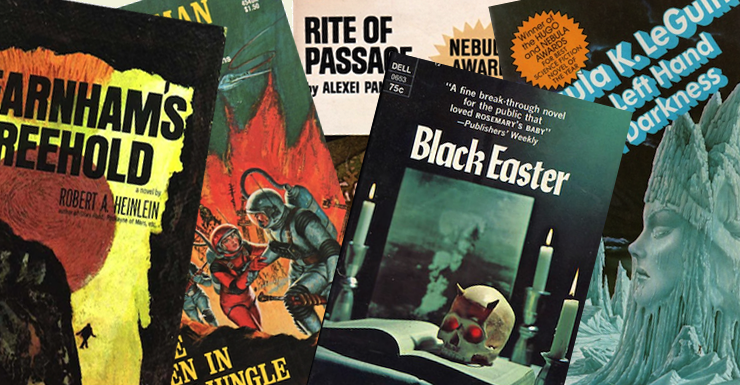

Some librarians must have grokked that some of Heinlein’s books were kinda racy. At least, someone seems to have been sorting them into kids’ and adult books, in my experience: stuff like Stranger in a Stranger Land or I Will Fear No Evil went upstairs, where only the adults and suitable mature teens were allowed. (I can’t recall how old you had to be to check out the adult-ish books, but I do remember it was annoyingly old from my perspective.) There were, however, occasionally bugs in the sorting system; Farnham’s Freehold ended up down in the kids’ section. The first part was fairly conventional: After the Bomb meets Incest: Not Just for Ancient Egyptians Anymore. But then it morphed into…how to put this politely? A racist work I don’t imagine that anyone would benefit from reading. Much less a ten-year-old.

Some books on the effects of nuclear weapons (not SF, but SF-adjacent) did make it into the kids’ section. These were not the delightfully math-heavy versions I discovered in high school. But the books did have pictures, as children’s books should… these were pictures from places like Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or from boats like the Lucky Dragon. When, years later, I encountered H. Beam Piper’s fiction, those pictures helped me appreciate the effects of Piper’s hellburner missiles on a visceral level. When I was six, the books helped me worry about planes overhead …which might be preparing to drop the Bomb on us.

My grade school3 had a policy NOT to buy books aimed at readers above a certain age. Again, though, the system wasn’t perfect. As well as Jeff and Jean Sutton’s The Beyond and various Franklin W. Dixon books, they stocked the full version of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. That may have been due to someone’s notion that kids should know that the expurgated picture-book version (also stocked) was not the real thing.

Moby Dick isn’t SF, but the manner in which it includes readers—infodumps the size of the white whale itself—may have predisposed me to like SF. Which, as you know, Bob, is also prone to humongous infodumps. Trying to read Melville in grade four may also have pre-adapted me for life as a reviewer: I understood early that life is too short to finish reading everything I begin.

How Norman Spinrad’s The Men in the Jungle, which features drugs, violence, and infanticide, made it into the children’s section, I don’t know. Is there anything by Spinrad that is child-friendly? That was indeed a traumatizing book to encounter when I was prepared for something more along the lines of Blast-off at Woomera. If I think about that Spinrad book now (even though I am older and somewhat hardened) I still feel queasy.

James Blish’s Star Trek script adaptations put him firmly into the children’s section as far as public libraries were concerned. It must have seemed only logical to place next to those books Blish’s other work, including his theological SF novels (A Case of Conscience, Black Easter), not to mention the more-sexist-every-time-I-read-it And All the Stars a Stage. Ah well, doubtless reading these books built character … if understood. Perhaps they were just baffling.

On the beneficial side of the ledger:

Alexei Panshin’s Rite of Passage probably looked fairly safe to the library’s gatekeepers. For the most part it fits nicely into the coming of age mold of so many YA SF novels. It was a little surprising when the young protagonist has sex with another tween during the rite of passage… but that was character development, not titillation. The plot development that did surprise me was the abrupt genocide inflicted on one helpless world. Mia, the novel’s protagonist, decides that all people are people, not just those on her privileged class, and that mass murder, even if the folks on the planet are free-birthers, is wrong. That’s not a bad moral for a book. I also appreciated Mia’s conviction that even long-established rules can be changed by sufficiently determined activists.

Earthsea established Ursula Le Guin as a kid’s author as far as the local authorities were concerned. Every fiction book she wrote ended up on the ground floor of Waterloo Public Library, where the young people’s books lived. This is where I first encountered The Left Hand of Darkness. Genly Ai’s adventure on an ice-covered world populated by people of varying biological sex was certainly an interesting change of pace from Freddy and the Baseball Team from Mars, The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet, and Star Man’s Son, 2250 A.D.

I never questioned the Le Guin policy; never asked the librarians, “Have you actually read these books?” This was payback. Supposedly wise adults had introduced us young’uns to apparently age-appropriate works like Old Yeller (the beloved dog dies), The Bridge to Terabitha (the beloved friend dies), and The Red Balloon (the magical balloon dies). Not to mention On the Beach, in which everyone dies AND the romance plot fizzles (because the romantic leads die). If their oversight greatly expanded the range of subjects found in the children’s section beyond a seemingly endless cavalcade of sudden tragedy, I wasn’t going to spoil the game by pointing their error out to them.

Buy the Book

Worlds Seen in Passing: Ten Years of Tor.com Short Fiction

1: Books that looked anodyne but weren’t were counterbalanced by all the non-sexy books with covers depicting naked people (naked people who appeared nowhere in the book—trust me, I checked). I could offer examples (the gratuitous bare-breasted cover for The Flying Mountains, the naked-woman cover of Methuselah’s Children, the full-frontal guy on that one cover of Stand on Zanzibar) but I am not sure Tor.com wants to post NSFW art.

2: My parents let us read anything we wanted, which is why the first stories I read from Arthur C. Clarke and from Larry Niven were in the December 1971 and August 1970 issues of Playboy, respectively. It’s also why, when my school assigned us The Pearl, it would have been very useful if they had specified “the John Steinbeck novel, not the well-known publication reprinted by Grove Press.” Beforehand, I mean. I understood my error after the fact.

3: North Wilmot, I mean. My previous school, Josephsberg, had a tiny library (supplemented by the occasional bookmobile) and the filter was more effective there because there were fewer books to filter. That said, I still recall reading a graphic, horrifying history of Fulgencio Batista, so it wasn’t completely trauma-free.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nomineeJames Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.